Anyone honestly curious and concerned about what is happening “down south” these days may wish to purchase a recent book put out by the Ateneo de Manila University Press. Arli Nimmo’s “A Very Far Place: Tales of Tawi-Tawi” is about his long sojourn as a graduate student in this wonderfully distinct place of hundreds of islands and islets. He writes about communities whose notions of boundary are antipodal to how the rest of the country understands the term.

Where Manila and Kuala Lumpur classify residents of Tawi-Tawi and neighboring Sabah as “Filipinos” and “Malaysians,” respectively, the inhabitants see these official tags as skin-deep and their utility limited (to be brought up only during elections and when they pass official immigration posts). Instead of these “modern” categories, they are comfortable with how they really call themselves—Tausug, Sama Dilaut, Sama Delaya, Kazadan, etc. These are identities that persist and to which a new layer—citizenship—would be added.

Hence, where Manila and Kuala Lumpur see Tawi-Tawi as “a far distant place,” the communities in these places (if we add Borneo) regard their location as one of many nodal points of a maritime trading network that predates as well as transcends the constricting official national territories. Theirs are places that are regional in outlook, a fact often glossed over.

Older than nation state

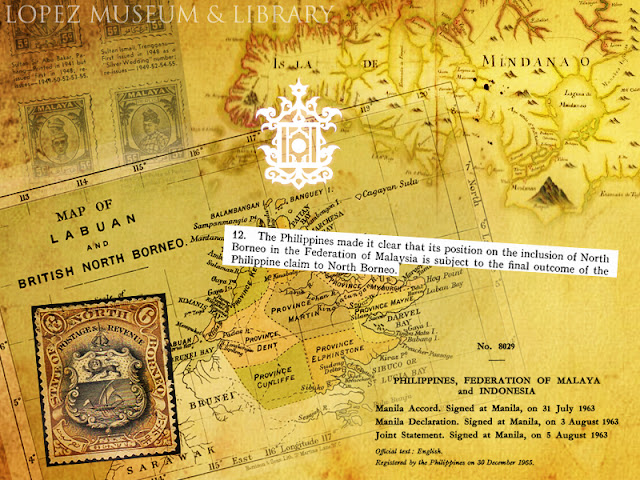

The authority that was part of a network of city ports lording over this domain naturally mirrored this older history and this wider world. The Sulu Sultanate is historically older than the Philippine nation-state, the Sarawak of the White Rajahs and the Sabah of the Malaysian Federation.

The sultanate outlasted the Spanish colonialists and sought a treaty with the British commercial syndicate that was running North Borneo (a corporation) as a way of reinforcing its position. But in so doing, the Sulu Sultanate weakened itself, such that by the time the Americans came Jamalul Kiram had signed a treaty with British North Borneo, ceding parts of his domain in exchange for an annual subsidy of $5,000. The Americans added to the predicament with yet another treaty signed by a middle-ranking officer (no worth to Manila or the US War Department) and the Sultan of Sulu.

All this may be a series of setbacks, but the series of retreats that considerably reduced the sultanate’s domain was understood not in national terms. The sultan never saw himself as Filipino. He lived in Sulu, but his other residence—during the first decade of American rule—was in Singapore, one of the many trading ports where he used to conduct business. So, it is a mistake for current-day commentators to insist that this Sabah claim was a rightful claim of the Sulu Sultanate as a Filipino entity.

No other option

It never was. Well, until the sultan’s heir and relatives realized that their Southeast Asian world had completely disappeared as the various colonial powers consolidated their territorial stakes in the region. With Singapore closed, Borneo under British mercantile regulation and the Americans and their Filipino allies adamant in keeping Muslim Mindanao a formal part of the Philippine geo-body, there was no other option but to become Filipino.

In short, the Sulu Sultanate of today is not the same as it was over 100 years ago. Then, it was a Southeast Asian entity; today, it is a Filipino caricature of its old self, a museum piece that national historians and ideologues would show to the public as yet another evidence of the unstoppable march of national (and modern) unity.

Speaking in Filipino

And what ironically exemplifies this poignant transmutation is the current sultan himself: living in Taguig in Metro Manila and speaking to the public not in Tausug or English (the language taught to his elders by the Americanos), but in the national language—Filipino!

But even mutations can retain the mental footprints of their old selves. When Jamalul Kiram III ordered his brother to arm 100 of their men and seize the small town of Lahad Datu in Sabah, he supposedly acted on a “historic claim,” Sabah being owned by the sultanate. But why did Kiram and followers opt to “capture” a small inconsequential town two hours and 45 minutes by car from Sandakan? Why not attack it instead (or Semporna)?

No Bud Dajo

There is no record of Lahad Datu as having the same stature as Jolo, and even today its claim to (small) fame is being the “base” of the Borneo Child Aid Society and a palm oil industrial cluster. And it is definitely no Bud Dajo, that village where hundreds of defiant Tausug—men, women and children—died fighting the Americans (a feat that is now part of the lore of struggle of the Bangsamoro).

Moreover, mustering 100 people in the Mindanao war zone is not really unusual. The clan wars (rido) that Asia Foundation has amazingly tracked could easily involve family armies that can run in the hundreds. What is sadly noticeable about the Lahad Datu occupation is how much the Sulu Sultanate has really diminished in name: the Kirams could only muster a force of 100! Even Umbra Kato, a renegade commander of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), has more men under his command.

But still, why do it? And how could a doddering authority still convince 100 men to bring out their motley arms and dare challenge a much superior force?

Weak state presence

Here, we find a bizarre melding of an antiquated authority that is now firmly Filipino (the sultanate) with two other realities in the Sulu zone. On the one hand, there is the consistent failure of the Philippine nation-state to assert its authority and gain the consent of its supposed subjects on this distant frontier. On the other, as a result of weak state presence, an everyday life that was still rooted in a regional maritime frame (this despite the selling out or compromises of their traditional elites) continued to persist.

Nimmo described this pathetic government presence this way: “The Philippine Air Force maintained a skeletal outpost on Sanga-Sanga Island where commercial flights of Philippine Airlines were scheduled to arrive twice weekly but often did not. The Air Force base had a jeep as did the small Philippine Navy base on Tawi-Tawi island….”

Mindanao war

No wonder then that when I chanced upon two Malaysian air force officers taking graduate studies in the Naval Post-Graduate School in Monterey, California, almost a decade ago, they reminisced—quite fondly—about how it was easy for them to transport guns from Sabah to the camps of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) at the height of the Mindanao war in the 1970s.

Things hardly changed a few years after that when, in a visit to Tawi-Tawi, the only visible government presence I saw was a poorly refurbished Philippine Navy ship that probably first saw action in the Korean War.

(Alongside Nimmo, a great read—because I think it will not be surpassed for at least a decade—is the writer Criselda Yabes’ “Peace Warriors: On the Trail with Filipino Soldiers,” a superb compilation of field notes of her visit to AFP camps in Muslim Mindanao.)

Mistrusted

In many villages of Muslim Mindanao, the Philippine state is hardly acknowledged and in the war zones highly mistrusted; people’s first encounter with government was a soldier with a weapon, shouting at them in a strange language (Tagalog, oftentimes Ilocano) and ready to fire at their homes. There were no civilian civil servants at all and if ever there were public school teachers brave enough to try to educate the children, they were hampered by the lack of resources because local politicians had run away with the payroll.

The absence of the state naturally means the refusal of opportunistic business enterprises to expand into these southern borders, leaving the premodern regional maritime trade as the only viable source of livelihood. The modern nation-state has naturally branded this as illicit and criminal, but because its enforcing mechanisms are pathetically laughable, communities continue with it, perhaps a little bit mindful that the occasional “raids” may eat into their revenue.

Cousins, families

Territorially, this means that national boundaries are of no concern, and cousins, families and business partners from both the Borneo and the Sulu side saw no need to worry about national identification cards.

It also means that even as the majority prefers to stick to commerce and trade, there will still be those who regard business as the product of tradition. The people who joined the petite uprising are most likely those who consider their lives inextricably linked to an “old tradition,” which sees their family histories as inextricably linked to an authority that was neither Malaysian nor Filipino. It is a primordial sentiment that has not been erased because the absence of the national state (particularly the critical educational apparatuses that could change young minds) made sure that it would be preserved.

But the speed with which this rebellion—so overrated in Manila and Kuala Lumpur—was stamped out also suggests the fragility of this old mentality. A few shots, some killed and wounded, and everyone appear to head home.

Or perhaps there is also another complementary explanation. The shootings may have surprised them, but the Sabah police most likely knew that the tension was easy to defuse. After all, those armed men at the other side of the checkpoints, were probably their relatives, business associates, even neighbors. Companies that they and their families have known and kept long before there was this imagined border that separated Borneo from Tawi-Tawi and the larger Sulu archipelago.

This brings us to a final point to consider. If this small town occupation was of historic significance, why are the two important Muslim Mindanao players keeping a distance from the Kirams and their men? Neither the fractious MNLF nor the far-stronger MILF has sent any of their battle-scarred companies to join the Kirams. And we have not heard any statements of solidarity from the spokespersons of these “movements.”

Pragmatic Moro politics

The silence, I suspect, has something to do with pragmatic politics. Like the old sultan, these two organizations have made their peace with Manila and have accepted the offer of autonomy. The MNLF and MILF are—despite misgivings—happy to be part of the Philippine geo-body.

But being movements borne out of more modern ideologies, these two organizations have very little to be in solidarity with the Sulu Sultanate. The MNLF’s secular ideology sees the sultanate as the very archaic, feudal power that had collaborated with Filipino colonialism to exploit, marginalize and repress the umma, while the MILF treats this “indigenized” political authority as pre-Islamic and hence, backward.

Besides, both would always be grateful for the Malaysian government’s support for their separatist struggle in the past. Why bite a hand that used to feed them? And why waste resources on something that had no prospects of even making a dent on Malaysian stability?

The skirmish is over and the border zone will be, as it were, back in business once again. And Manila and Kuala Lumpur may find it just prudent to let things be, to let the locals deal with the quirks of an existence, which hardly matter to the two capitals.

(Patricio N. Abinales is professor of Asian Studies, University of Hawaii-Manoa. His latest book is “Orthodoxy and History in the Muslim Mindanao Narrative” [Ateneo: 2010]. He is working on a manuscript on the Growth with Equity in Mindanao [GEM] and the American economic presence in the war zones of Muslim Mindanao. Despite his current address, he remains an official resident of Ozamiz City, northern Mindanao.) - source